What Was I Thinking?…

I joined the Royal Navy on September 15th 1971. Three days later, marching up and down BRNC Dartmouth parade ground at 6:30am under floodlights in the pouring rain, I really did wonder ‘what was I thinking?’

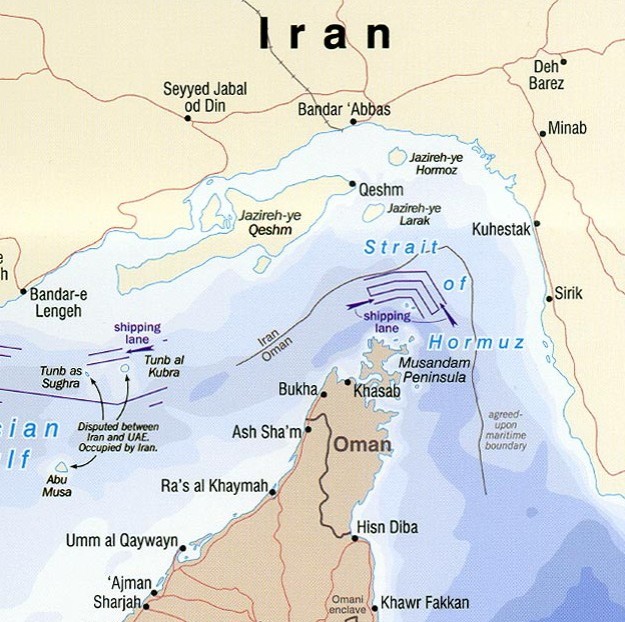

Well, let’s see. I grew up and went to school in Bletchley, Buckinghamshire with a brief 3 year stay in St. Neots, which was then in Huntingdonshire. Both hardly near the sea, in fact the only time I saw the sea was when we went down to Cornwall for holidays, or on the cross channel ferry to France. Bletchley, as we now know, was the main codebreaking centre during WW2 – something that was still secret when I was at school, and I daily walked past Bletchley Park (by then a Post Office Telecommunications training centre) blithely ignorant of what had gone on in there.

Bletchley Park

I did have some naval/military connections. My Grandfather, Charlie, was one of those men who was born in 1900, and he joined the Navy as a boy stoker in 1915 serving, amongst other ships, in HMS Warspite – post Jutland – when he was 17. He stayed in for a full career, serving in MTBs during WW2 and eventually retiring as a Chief Stoker in 1955. My dad’s brother, Bob also served in the RN in the 1950’s and left as a Leading Hand after 12 years to go on to have a long career in the Fire Brigade, and my Uncle Tom was a Warrant Officer in the Army. I don’t remember ever having a serious conversation with any relative about joining the military – in fact I kept it a bit of a secret at first.

By the autumn of 1970 I’d had enough of school. I was at Bletchley Grammar School, and having done my GCE ‘O’Levels the year before, I elected to stay on to the Sixth Form and sit two science GCE ‘A’ Levels. This was to the surprise and, frankly, dismay of my family, all of whom had left school at 15 and gone out to work. I think I was expected to take my ‘O’Levels and then leave and get an apprenticeship or something that brought in a wage so I could contribute to the family income. Anyway, by early 1970 I’d got a job packing paper rounds for a local newsagent – a job that involved getting up at 4am, working to 7:30 then going to school. By lunchtime I was nodding off in class, and frankly not taking much in. One morning, I saw an advertisement for RN Artificers (engineers) in one of the papers, and on a whim I cut out the coupon and sent it in. Two weeks later I had a reply and a rail warrant to Watford for a preliminary interview at the RN recruitment office. I called the office, agreed a date and time and jumped on a train, having said not a word to my parents or friends.

When I walked into the Watford recruiting office, my first impression was how smart it all was. Posters depicting modern naval life were on the walls and the staff were friendly and welcoming as I sat down to wait. I was called into a side room by a Chief Petty Officer – I only knew that because he told me – who then asked me to tell him about myself, my interest, hobbies, why the Navy, pretty standard stuff. He then outlined what Artificers did in the Navy, how long the training took, career prospects, and by that time it was clear to me that this wasn’t what I wanted. I didn’t want to be an engineer down in the bowels of the ship like my Grandfather; I wanted the sun on my back, to fire guns and missiles, to see where I was going. I wanted to be a sailor. Maybe. Actually as the interview went on, I didn’t know what I wanted and said this to the Chief. The Chief got up and said “OK, no problem, let me talk to my boss”, and left the room. Sometime later, he returned and said “The boss wants a word” and led me down the corridor to meet The Boss.

The Boss, it turned out, was an SD Engineering Lieutenant Submariner. SD stands for Special Duties which means he was promoted from the ranks, in his case from PO Artificer (SM). We chatted and finally he said, “Look, I see here that you’ve got 8 GCE’s – that more than qualifies you to apply for a short service commission”. An officer… I’d never thought of that, so I asked him to tell me more. At the end of it, a short service commission in the Royal Navy sounded just the ticket. The boss advised me to apply for the May 1971 Admiralty Interview Board (AIB), and that I could also apply as aircrew if I so wished because whether or not I was selected for flying training, I could probably still do the AIB. I learned much later that the RAF was switching to all graduate aircrew recruiting, and the RN, desperately short of junior and middle ranking non-career specialist officers, were hoovering up potential talent by only requiring ‘O’ Levels for short service seamen and aircrew. Those that failed the aptitude tests at RAF Biggin Hill were, at the discretion of the liaison officer at Biggin, offered an AIB for seaman specialist. The newly planned aircraft carrier, CVA-01, and all but one of its escorts had been cancelled four years earlier; the future for the Fleet Air Arm seemed to be rotary wing only, with a smaller surface fleet concentrating on Anti-Submarine Warfare in NATO waters. Long term career prospects were becoming limited and let’s face it you don’t need a degree to fly a chopper or stand on a bridge. So I went home, told my parents what had happened, filled out the application for a short service commission, went back to school and waited.

Before I go any further, let me describe who I was back in 1971. Basically, I was a typical, white, lower middle class, 18 year old long haired bell bottom and grandad shirt wearing product of the ‘60s. I wore John Lennon sunglasses and rode a Lambretta scooter. I mourned the Beatles break – up, was into Cream, Rod Stewart and The Faces, T-Rex and The Stones. Laugh In, Monty Python and the Two Ronnies were on the telly, John Peel and Kenny Everett on the radio. The Kennedys had been assassinated; Neil Armstrong had walked on the moon, the Vietnam War dragged on with Nixon in the White House, Ted Heath in No. 10. I played a lot of sport, rugby for both the school and town, swam a lot and was (so I thought) pretty fit. I couldn’t drive a car, had only been to sea on a ferry and had flown in a plane – a BEA Trident – once. So obviously I opted to join the Royal Navy as a helicopter pilot. Go figure.

Just after Christmas, I received a large pack of documents to read, sign and send back. There was also a guide as to what to expect at the AIB, travel directions to RAF Biggin Hill and the necessary warrants. There was also a recommended reading list, instructions on what to take with me and a guide to the fitness levels required for entry. Interestingly there was also that spring a BBC documentary on BRNC that gave me a good, if rather sanitised, insight on what I may be in for. So one Tuesday morning in May 1971 I set off, not for Portsmouth but to RAF Biggin Hill in Kent for flying aptitude tests prior to the AIB.

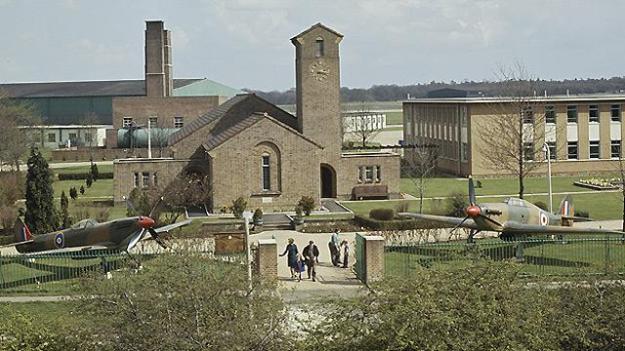

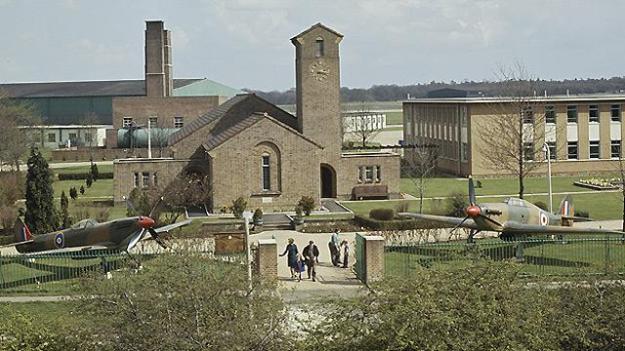

RAF Biggin Hill

As anyone will tell you, even today, the Royal Air Force is run by officious, bitter, short-arsed corporals who wish they were flying fighter jets and angry that they don’t. They are particularly angry with potential officer recruits, whom they regard as jumped – up public and grammar school boys trying to fast track themselves to the top. Their attitude was clearly “If you want those wings matey boy, first you’ve got to get past me”. The flying aptitude tests took a day, so as I had arrived the night before, I dumped my bag in my room and found the ‘Candidates Bar’. The next morning I turned up at the test centre with a mild hangover and no idea what was going to happen next. What happened next is that a corporal called out names to go into groups of six or so. When he had finished there were about five of us left standing. The corporal looked across the room and said “Oh yes, you lot. You’re Fleet Air Arm. Go over there and wait”. My dislike of all thing Crab started right there.

Crabs

Eventually, a tall, blonde haired Lieutenant in number 5 uniform (eight button jacket – no woolie pullies in the RN until 1973) with pilot’s wings on his left sleeve turned up. He grinned and said loud enough for the RAF types to hear, “All those for the Senior Service follow me”. We swaggered out, natch. The tests started with a film on the theory of flight, followed by a series of paper tests with diagrams of instruments, views of aircraft in flight which you were supposed to translate into stick and rudder inputs and there were mental arithmetic tests, mostly speed/time/ distance problems, number sequence recall tests and some verbal tests. The one thing I vividly remember was something we’d now call a crude video game. Basically you sat in a chair with a green video screen in front of you, and a joystick and rudder pedals that you could move with your hands and feet. On the video screen was an illuminated circle about 15 cm in diameter with a dot inside it that responded to the stick and rudder. All you had to do, said the corporal, was to keep the dot inside the circle. When the test started the dot began to move out of the circle which required me to move the stick and rudder to correct the drift. Every time the dot got out of the circle it was recorded on a counter on Corporal Crab’s desk. Any kid doing this test today would probably fail because he’d be falling about laughing, but in those days there were no video games, and I found the test extremely challenging, just as I can’t do shoot ‘em up video games now. My hand/eye co-ordination is not good enough, something I should have known, and something that would bite me again, as I was rubbish at golf, cricket and tennis and still am.

After the tests, we walked across the base to the RN offices and awaited the verdict. I was called in to the RN liaison officer’s office and sat down. This is where I learned that the RN always gets straight to the point. The liaison officer, a passed over (i.e. didn’t make Commander) Lieutenant Commander with Observer’s wings, looked at me, looked down at the results page, looked up and said, “ Well Fenton, you’ve failed. Quite badly on the hand/eye and aircraft attitude, and these results indicate that flying’s just not for you.” I wasn’t surprised. You either have good hand/eye co-ordination or you don’t. Evidently, I don’t. “However” he said, “You did OK on the maths and Lt. Blondie was quite impressed with your verbal tests and your general attitude, so we are offering you a place on the AIB as a short service seaman officer candidate. We need your answer now, transport leaves for Portsmouth in an hour”.

I said yes, fine.

AIB

I arrived at the AIB – which is part of HMS Sultan in Gosport – at about 7pm that day. On the train down, Lt. Blondie took the three of us (two had gone home) into the bar area, and over a can gave us some insight as to what was next and some tips on getting through the process. One of the things he emphasised was to talk to the staff – particularly the Leading Hands and the Able Seamen who rigged the practical tests. Nobody wanted anyone to fail, he explained, and the board were looking for attitude as well as aptitude. The Navy wasn’t bothered with who you are now, but who you have the potential to become. I was struck by the contrast between this informal, friendly approach and the cold, mechanical approach from the RAF corporals. When I got there I signed in and was shown round the AIB and where my room was. Then there was a briefing by an officer and a senior rating, supper and we were told that the rest of the evening was ours. Taking Lt. Blondie’s advice, me and a couple of others went to the Cocked Hat pub across the road where we found a couple of the ABs who worked at the Board, bought them a pint and had a chat. They told us not to be nervous, be bold in the practical tests but not stupid, don’t bully anyone and don’t act like a prick. They also told us what test had been rigged for us on day 2. Very useful. I later learned that they reported back to the Senior Rating and It Was Noted.

The Cocked Hat

I’m not going to go into the minutiae of what happens on an AIB as all anyone needs to know is on countless message boards and it really hasn’t changed much over the years. What we got was a briefing after breakfast and then straight in – Day 1, Verbal and non-verbal reasoning tests, numeracy tests, special awareness tests, general knowledge tests and then a 45 minute essay from a list of topics. Then lunch. After lunch we were briefed on the Practical Leadership Test, which most people have heard of. It involves working as a team to get an object or person over a barrier within a set time without touching the floor. Then there was a gym session and a run (I believe it’s a bleep test these days) and finish. The first half morning of day 2 was the PLT, which as a former Boy Scout I really enjoyed, and then there was a slightly weird chat with a shrink, a really complicated team planning exercise, and finally the interview with the Board. The Board I sat in front of in my Burtons suit consisted of the President, a Rear-Admiral, his deputy, a Captain, two Commanders, one playing Mr. Nice Guy, the other playing Mr. Nasty, Claude Littner – style, the shrink, a WRNS officer and a public school headmaster. It took about 30 minutes and again I rather enjoyed it, as anyone who knows me knows I love talking about myself. I remember Mr. Nasty at one point asking me ‘why the Navy?’ to which I replied ‘because I like what I see so far’ to smiles all round. At the end, I picked up my bag, collected a travel warrant and went home. I understand that nowadays candidates are now told the outcome of the board before they go home, but we were told we would be informed by letter in about three weeks. There were twelve of us that day; I remember going out of the door with a cheery “See you at Dartmouth!” more in sheer bravado than in any confidence.

As we new entries gathered on the Quarterdeck at Britannia Royal Naval College, Dartmouth on the 15th September 1971, I looked around to see if I could recognise any of the other candidates from the AIB. None of them were there: I was the only one that got in.

Turns out, getting into the Navy was harder that I thought. Staying in, I soon discovered, was going to be a whole lot harder.